Mr. Robot's "Reality" Monologue

How to Pack a Punch in Your Writing

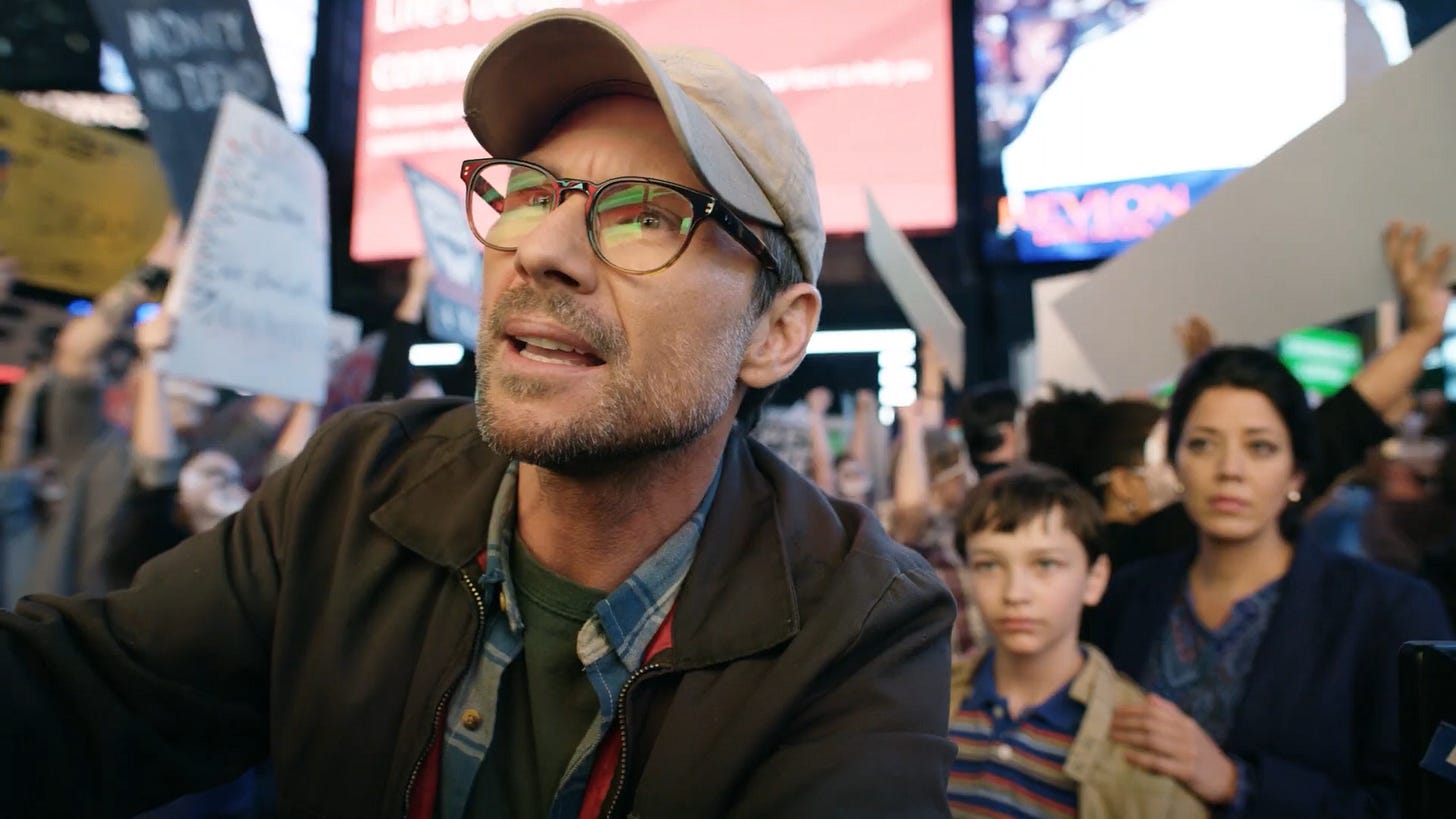

I’ve recently rewatched Mr. Robot, a high-octane, high-impact show about an anarchist hacker who broke his brain into two trying to thwart a megacorporation as a means of destroying debt bondage and wage slavery.

The plot of tunnel-visioned conspiracy theorists having their paranoia be manipulated to further the ends of the very same political entities they’re trying to oppose hits way too close to home.

In the show, a hack brought the world economy to the brink of collapse. In real life, it was a virus. In both, it had something to do with China. It is morbidly funny how much the show still holds up.

With its oppressive negative-space cinematography, the wonderful plethora of Marxist motifs, the ceaseless gaslighting of its plot, and heartbreaking themes of parental abuse, Mr. Robot is going to be remembered for a long time.

The episodes were always something to look forward to, but the parts that really stuck to me were the internal monologues. The lines written and the lines delivered were so visceral, so raw, so unapologetic that they immediately grabbed your attention and refused to let go.

They are a masterclass to a man.

For this article, there’s a speech I want to take a scalpel to. It’s the one that took place on the last episode of the first season.

I’ll try keeping spoilers to a minimum, but essentially the two central characters finally come to blows, and what sets off is a soliloquy that’s about as venomous as a rattlesnake.

ELLIOT: You’re not real … You’re not real.

MR. ROBOT: What, you are? Is any of it real? I mean, look at this. Look at it!

What a great monologue in the modern age needs before it can truly begin is a trigger. A monologue that happens for no reason and with no solid foundation cannot work.

A monologue is powerful if it’s a direct response to a character’s challenge. And here, Mr. Robot was challenged on the grounds of “reality”. The watchword of the day.

Characters should preferably be on opposing sides or have vastly different views, which the show achieves in full effect. Elliot and Mr. Robot have the same viewpoint in more ways than one, but they reach an impasse when it comes to approach. Elliot may be a radical, but Mr. Robot is a full-on extremist.

And so his grandstanding monologue can finally begin in earnest:

“A world built on fantasy! Synthetic emotions in the form of pills. Psychological warfare in the form of advertising. Mind-altering chemicals in the form of food. Brainwashing seminars in the form of media. Controlled isolated bubbles in the form of social networks…”

God, the beautiful mesh of politics and coder lingo is just the best. The best. These sentences live rent-free in my head, and that right there is the high-rent district. As it keeps going and going, you can sense a rhythm, right? Mr. Robot is a beat poet, and the beat goes on. Adding a lyrical quality to your writing gives you something to bounce off with, such as this.

Props to the actor Christian Slater for making the character come to life, and props to the show’s editors for making it look like Mr. Robot’s train of thought is talking so fast it’s almost as if he’s interrupting himself just to get to the point, like your typical political pundit.

Let’s not tarry too long and continue:

“… Real? You want to talk about reality? We haven't lived in anything remotely close to it since the turn of the century. We turned it off, took out the batteries, snacked on a bag of GMOs while we tossed the remnants in the ever-expanding dumpster of the human condition…”

Mr. Robot strategically returns to the subject of reality because, remember, that’s the whole point of the argument, that reality itself isn’t real, that control is an illusion, and that we’re all being whisked away to a material apocalypse unless we do something about it.

Keep this in mind: a character needs a hill to die on. It is what signifies their passion, the sort of character writing that can move your viewers or scare them, but all that matters is that it affects them. That’s the goal.

Without further fuss, let’s head to the last gut-punching part of the monologue:

“… We live in branded houses trademarked by corporations, built on bipolar numbers jumping up and down on digital displays, hypnotizing us into the biggest slumber mankind has ever seen. You have to dig pretty deep, kiddo, before you can find anything real. We live in a kingdom of bullshit! A kingdom you've lived in for far too long. So don't tell me about not being real. I'm no less real than the fucking beef patty in your Big Mac.”

It reaches a boiling point. We can see, through the opacity of his character, that Mr. Robot is bitter, rageful, and motivated as an idealogue trying to usher in his revolution. You can hear how passionate he is, and passion can be downright contagious. The moment is intoxication enough, and that’s what this style of storytelling is at its core: a moment-maker.

Now, the dangers of trying to create a “big moment”, like a monologue, is that it might turn into something artificial. It’ll feel flat if you rush into it. High risk, high reward. There’s a chance your audience might leave feeling a little deflated, and they’ll start asking why they’ve been wasting their time following along a contrivance.

Good writing is about focusing first on constructing a steady plot progression and hand-crafting motifs, only writing a moment of spectacle when it’s earned and ready. But when is it ready? Well, now we’re shifting our focus to the placement of a monologue. You can place a monologue in the beginning to set the tone for the story, in the middle to signify a paradigm shift, or in the end where it can reach its full potential and draw the story to a close.

Succeeding in this endeavor will have a lasting impression on your audience. The whole purpose of analyzing this is not to make our writing perfect, but to make it perfectly imperfect. So good luck, and hopefully this was of some use to you for your next project.

there are so many good nuggets here, but I really like, "your character needs a hill to die on"

It was a pleasure finishing this show before it left Netflix, haha. Such good writing, agree.